Auditory Brainstem Implant ABI: Hearing after an acoustic neuroma

MED-EL introduced its first brainstem implant, also known as the Auditory Brainstem Implant ABI, 20 years ago. Civil engineer Markus Friedl has been hearing with a SYNCHRONY ABI from the Austrian implant manufacturer for two years.

Eva Kohl

Behind an abandoned allotment site, a crane towers far into the clouds in the distance. In front of it, sorted into piles, the waste materials salvaged from the excavation are waiting to be transported away. Despite the large machines, it is surprisingly quiet on the construction site in the late afternoon. Only every few minutes does the engine of a truck hum as it rolls along the narrow access road. "Watch out for the trucks!" warns engineer Markus Friedl. He works here in site management. You should be able to hear the lorries so that you can take evasive action in good time, even if a lorry is coming from behind.

Markus Friedl also benefits from the noise suppression of his ABI audio processor at his noisy workplace. ©Adobe Stock

About fifty meters behind the construction site you come to the site management container. This is where Friedl's office is located, as well as the meeting room with the construction plans. "I'm in a job where it's important to understand others," he explains. "Here at meetings and out on the construction site." However, he lost his hearing 15 years ago. He is completely deaf on his left side and only has residual hearing on the other. "Without a hearing aid, I can hear almost nothing on the right. No coffee machine. No flushing of the toilet."

Bilateral acoustic neuromas robbed the Lower Austrian of his hearing. Unfortunately, a cochlear implant did not seem to be promising for him. Since December 2021, the 42-year-old civil engineer has instead been hearing with a brainstem implant, or ABI for short. Although this implant is similar in function to a cochlear implant, it is rarely used in the special ABI design; the disease neurofibromatosis, which caused the neurinomas and deafness in the ABI user, is also rare.

Neurofibromatosis, a rare disease

It all started with a sudden hearing loss on the right side when Friedl was 28 years old. "It was first treated as a sudden hearing loss. The fact that an MRI was then also carried out was pure coincidence." Benign tumors were discovered on the auditory nerves on both sides. The doctors diagnosed central neurofibromatosis.

Neurofibromatosis, or NF for short, is a genetic mutation that is inherited in around half of all cases. In the other half of the cases, the change is "acquired", also known as "spontaneous": The chromosome responsible has mutated during embryonic development. First described in 1882 by the German physician Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen, NF is one of the so-called "rare diseases". These are diseases that are either life-threatening or chronic and affect a maximum of 5 in 10,000 people.

Experts distinguish between three types of neurofibromatosis: NF1, NF2 and schwannomatosis. A different gene is affected in each of these diseases. What all three have in common is a tendency to develop tumors in the nervous system.

Central neurofibromatosis often damages the sense of hearing

NF2, also known as central neurofibromatosis, which is particularly rare: one in 35,000 people is affected. NF2 is characterized by the occurrence of benign tumours of the nerve sheath tissue - so-called Schwannoma. This can affect various nerves, and vision can also be impaired; typical accompanying symptoms are headaches and nausea. In NF2 patients, however, benign tumors on the eighth cranial nerve, which is responsible for hearing and balance, are in the foreground. These vestibular schwannomas - or acoustic neuromas - can occur on both sides and also repeatedly.

Sometimes it is enough to observe such an acoustic neuroma. However, if it exerts pressure on the nerve or the surrounding tissue, this can cause various symptoms. The tumor must then be removed.

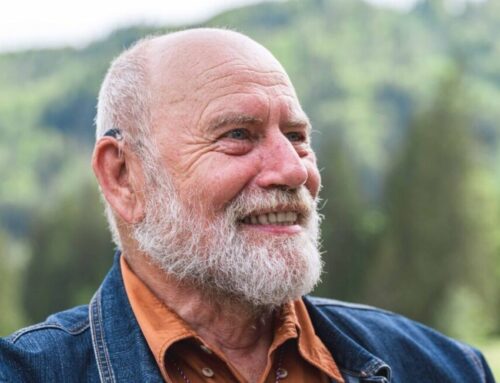

Civil engineer Markus Friedl: with his brain stem implant at work ©Eva Kohl

This was the case for Friedl in 2008, too. "My whole family was nervous." After all, this operation involves working on the nerve that controls hearing, balance and facial expressions. "But I wasn't scared. The surgeons who perform such an operation are absolute specialists." The ENT surgeon was even able to preserve some residual hearing on the right, but this was no longer possible on the left: "I can only communicate in a quiet environment with hearing aids in my right ear if I concentrate."

Back to hearing on both sides

Around five years ago, the Lower Austrian developed a new neurinoma in his right ear - the ear that was the only way for him to hear at the time. He was worried that the tumor would have to be removed and that he might lose the last remnants of his hearing. "That was the point when I started to find out what was available for my left ear."

Even in cases of unilateral deafness, specialists now usually advise those affected to have hearing implants. This is particularly true for NF2 patients, as there is still an increased risk of further neurinomas. This was also the case for Markus Friedl when he contacted the Wiener HNO-Universitätsklinik AKH. There, Prof. Dr. Christoph Arnoldner discussed the various implantation options with the patient. As Friedl's left auditory nerve was not only affected by the tumor but had also been inactive for many years, Friedl decided to have a brain stem implant straight away.

Even if the auditory nerve is not working: The sense of hearing can be regained!

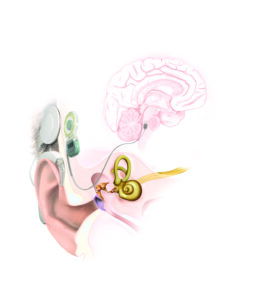

The sense of hearing is the first and so far only human sensory organ that can be artificially reproduced and replaced. Cochlear implantation, first performed in Vienna in 1977, is now a routine operation. It is also used successfully in cases of unilateral deafness and residual hearing. However, the prerequisite for this is the function of the auditory nerve. If this has been lost due to a tumor or an operation, for example, the option of an auditory brainstem implant (ABI) remains. The audio processor and implant are similar to those of a conventional cochlear implant. However, the electrode in the ABI is flat and is placed directly on the brainstem. From there, it stimulates the auditory regions in the cortex.

The SYNCHRONY ABI brainstem implant from MED-EL ©MED-EL

The MED-EL ABI for adult NF2 patients was introduced 20 years ago. Prof. Dr. Robert Behr, former head of the Department of Neurosurgery at Fulda University Hospital and one of the world's leading ABI specialists, recalls: "In the early days, it was believed that the ABI would only provide supplementary support for lip reading. There was no belief in open speech comprehension or free communication." After over 1,000 ABI implants worldwide, this view has changed. "ABI technology and surgical methods have constantly evolved over the past 20 years, enabling our users to hear better and better," explains MED-EL founder and CEO Dr. Ingeborg Hochmair. Today, many ABI users lead independent lives in the hearing world.

"When the batteries in the processor run out, the implant comes off!"

Sober facts about a treatment method are one thing, the individual decision to have an implant is something else. For Friedl, however, it was a clear decision: "I already had experience with demanding operations to remove tumors. And I thought to myself, my hearing can't get any worse." Two new tumors on the left nerve were also to be removed during the operation. "This removal worried me more than the implantation. And an ABI implantation is a rare procedure. I'm sure the best specialists in the world of surgery are involved." With a mischievous smile, he adds: "A chef doesn't let the apprentice touch the roast..."

Friedl's operation was performed by neurosurgeon Prof. Dr. Christian Matula, Head of the Skull Base Outpatient Clinic at Vienna University Hospital. From an ENT perspective, she was supervised by Prof. Dr. Christoph Arnoldner. The newly operated patient was allowed to leave the clinic after just a few days and soon felt fit again.

"The time afterwards was still exciting. The brain stem," where the flat electrode of the ABI was placed, "doesn't have a marker that says: You have to put the plug in there." The tonal arrangement is not as precisely recognizable on the brain stem as in the inner ear. This is why getting used to hearing with the ABI can take a little longer than would typically be the case with a conventional CI today. "I'm in no hurry," says Friedl calmly. "And when the batteries run out, I'm already very happy with the implant. For me, it's a clear sign that it's already helping me hear a lot."

Who can benefit from an ABI

An ABI can also help people who have become deaf for other reasons if the auditory nerve or its function has also been damaged: other tumors, for example, particularly extensive ossifications or head trauma. Since 2017, children from the age of 12 months can also benefit from ABI if they were born without a functioning auditory nerve.

This is how Markus Friedl benefits from his hearing implant: "In some meetings, it's still difficult to understand. And I can also hear the wind whistling with my two hearing systems," he admits. But then the civil engineer laughs as he talks about the effective noise suppression in the audio processor: "When it's really loud on the construction site, I sometimes even find it easier than my colleagues with normal hearing. Without this implant, I wouldn't be able to do my job today."