About the Art of Hearing – in Painting, Medicine and Cochlear Implant Technology

On March 3, 2023, on the occasion of World Hearing Day and its 30-year location anniversary, the MED-EL Vienna branch invited guests to the Belvedere Palace. There are several reasons why – all of them are related to art. A wonderful opportunity to take a closer look at the connection between fine arts and hearing:

International guests from various disciplines as well as companions and friends came together in March on the World Hearing Day in the famous baroque complex, which recorded its structural completion in 1723, exactly 300 years ago.

30 years MED-EL Vienna - 300 years Belvedere, a very nice coincidence, although actually a very specific lady was responsible for the connection between the hearing implant manufacturer and the Belvedere Palace: Namely the muse who was available to the famous Ringstrasse painter Hans Makart for his painting series "The Five Senses" at the time, more precisely for "The Hearing".

After 150 years, this lady is now somewhat older - thus MED-EL Vienna provided financial support for the restoration and therefore served as a thematically perfectly fitting godparent for the impressive painting.

Onomatopoeia over the centuries

Onomatopoeia over the centuries

Hans Makart's painting is just one example on this topic - representations about hearing, or listening, respectively, have been innumerable over the centuries. Among the most prominent painters of the Baroque period are arguably Jan Brueghel the Elder, Jan Steen, Gerrit van Honthorst or the incomparable Michelangelo Merisi - better known as Caravaggio.

They all dealt with the human senses in their works and usually hearing - as one of these senses - was placed in the center as the most important human sense. The depiction of music was particularly popular in this context due to its many symbolic meanings; it was considered a status symbol, especially in the 16th and 17th centuries. Musical instruments as well as people playing music were therefore often painted as a demonstration of wealth.

The view from the outside

The view from the outside

The theme of hearing in painting can however also be turned around. Out of silence numerous famous works were created, in which the absence of the so important sense of hearing can be seen:

The world that the painter Wolfgang Heimbach created is free of noise. One often notices this only at second glance, which makes his works even more fascinating. Only when you know that the North German artist, born in the 17th century, was deaf, do you realize that nobody strikes a lute in his idylls, no fanfares resound in the most beautiful scenes of homage. He often designed his depictions from the perspective of exclusion. In the possession of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna is his painting Nocturnal Banquet, which shows this impressively. At the same time, this work belongs to the series of chiaroscuro, whose dramatic expression was a special design device in the late Renaissance and Baroque periods. Heimbach thus concentrated strongly on the power of light and was influenced by the works of the Caravaggisti group - such as Caravaggio or the grandiose Georges de la Tour.

The dark romantic

The dark romantic

The works of Francisco de Goya are magnificently gloomy. The Spanish painter, etcher and lithographer became completely deaf after a stroke at the age of 46, thus his life as well as his creative work changed dramatically. His altered sensory perception and his associated withdrawal from society gave rise to nightmare-like works, which at the same time were his most famous ones. Most impressively, the graphic series Caprichos as well as Las Pinturas Negras, his Black Paintings, illustrate the artist's eerie mood created by his deafness. He originally painted these grotesque depictions of the Pinturas Negras on the walls of his country house; they are now transferred to canvas and can largely be admired in the Prado, Madrid's renowned art museum.

Pictures in the ear

Pictures in the ear

Another viewing or listening angle: Sitting. Listening. Seeing - Anyone who gets involved in this in Rita De Muynck's studio can get an inkling of what the artist wants visitors to her exhibition to experience - a deeper perception of art. The simultaneous activation of different senses, in scientific terms: synesthesia. De Muynck has been experimenting with this phenomenon for over twenty years. She listens to music in a trance-like state of complete relaxation, feeling and hearing primarily the colors, shapes and figures. Only later, days or months may pass, she puts the images on the canvas.

Visitors can sit on armchairs in front of the paintings, the artist turns on exactly the music at which she has heard-seen the paintings, and indeed the perception also changes in the viewer: Didn't the pink-red creature in the mysterious forest just move in time with the music? Does the light suddenly glow stronger? Does it crackle in the branches, does something pulsate and grow in size?

This experience is not to be confused with classical association, De Muynck emphasizes. It goes deeper, into the limbic system. "Art opens the brain," Rita De Muynck is convinced, thus demonstrating another very exciting symbiosis between hearing and visual art.

Hearing colors, seeing sounds

One person in particular was good at this: Wassily Kandinsky. Thanks to his gift of the aforementioned synesthesia, the ability of multisensory perception, he was able to create a connection between sounds, colors and shapes as well as to incorporate music into his paintings.

The Centre Pompidou in Paris and Google Arts & Culture have teamed up to pay tribute to the artist, who is considered the initiator of the abstract art movement. Sounds like Kandinsky brings his artwork together in one place and includes a new machine learning experiment called Play a Kandinsky that lets you experience for yourself Kandinsky's extraordinary ability.

Composed Paintings

Settings of paintings come in many forms: composers using paintings as inspiration for their music; concert formats pairing music with visual art to sensually and atmospherically expand the perception of art; artists telling the story of their own works - the possibilities for combining hearing and seeing in art seem almost endless.

With all senses - or of senses?

With all senses - or of senses?

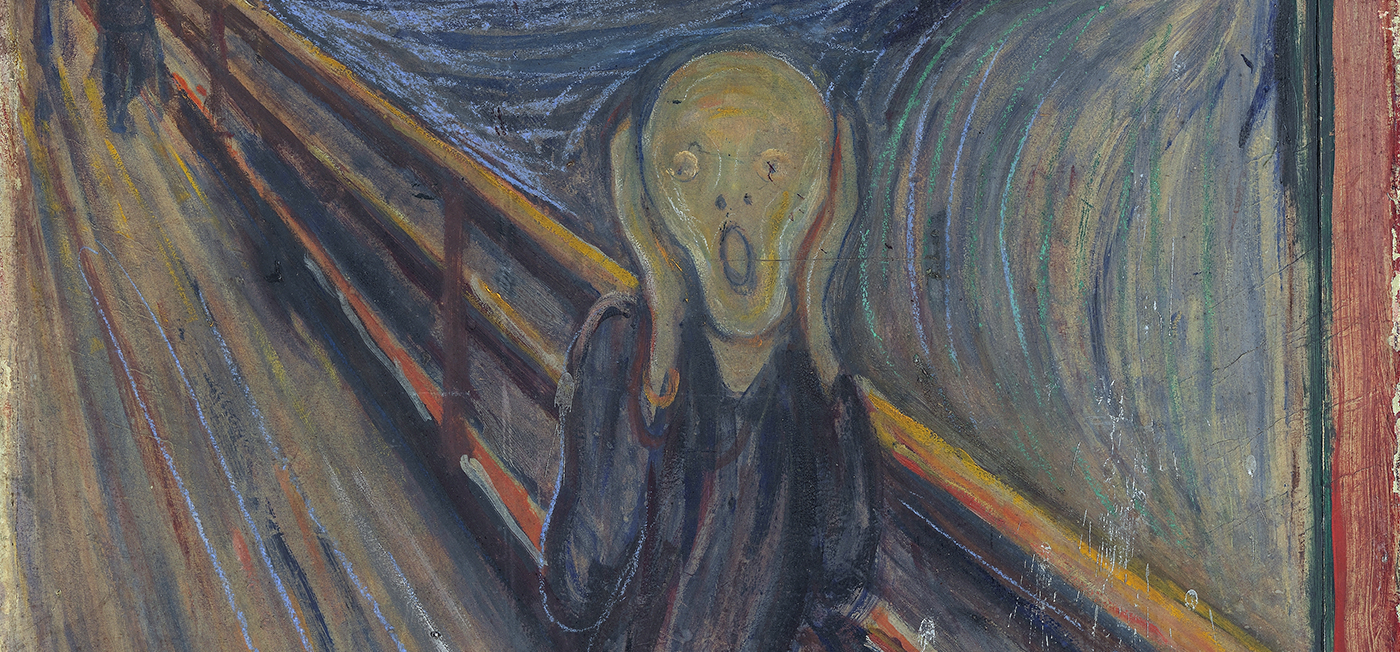

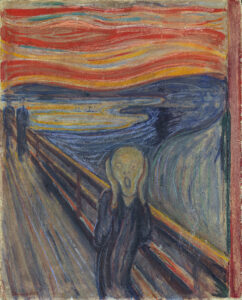

The Norwegian Edvard Munch's painting The Scream is probably a very appropriate example of an "auditory painting" and one of the most famous works of modern painting ever. Actually, it is not just one painting, Munch painted the scream over and over again in the course of 17 years, known are four paintings and one lithograph, which in variations always show the same thing: a person with a bent body pressing his hand over his ears and opening his mouth and eyes wide.

But why does someone who screams loudly cover his ears at the same time? At some point, the question arose as to who is actually screaming or not screaming. In the meantime, it has become clear that the figure in the picture is not screaming - instead, it is doing something else that, in this one moment, determines its relationship to the world more than anything else it might be doing: this figure is listening. Whereby it is actually not completely correct, because the figure is covering its ears. The scream is therefore too loud. And since the figure opens its eyes wide at the same time, this scream also seems to be visible. The background on the picture does not give a single hint to the obviously loud sound source. Only a place with waves, wind, nature - which nevertheless screams - is audible and visible. Or is the figure, due to its bent posture, out of its senses after all, because it hears the scream only inwardly?

After all, Munch has declared: "I felt the great cry of nature". So if you don't believe that pictures can be heard, you should take another look at Edvard Munch's scream until he or she can hear it.

The ear in the picture

As is well known, there are many speculations about Vincent van Gogh's cut-off ear. He cut it off himself in Absinth intoxication; no, it was his friend Paul Gauguin as a result of a bitter dispute. Various stories surround what is probably the most famous ear in painting, just like criminal cases.

What is certain is that on December 23, 1888, van Gogh, completely overworked and drunk, cut off a small piece of his left ear in the presence of his friend Gauguin. It could not have been the whole ear, otherwise he would have bled to death. With this interpretation, Van Gogh is not pushed too much into the corner of the mad artist either and the attention is focused on his great artistic work.

From this short excursion into the world of painting, which is inextricably linked to hearing, let's return to present-day Vienna, where MED-EL's sponsorship of Hans Makart's Das Gehör (in English: The Hearing) brings the art of hearing full circle; to a Vienna that has been producing medical excellence for centuries; to a Vienna that was the first in the world to artificially restore the organ of hearing. Not just artificially - through art & skill.